The Complaint of Venus Read in Middle English

| Geoffrey Chaucer | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Chaucer (19th century, held by the National Library of Wales) | |

| Born | c. 1340s London, England |

| Died | 25 October 1400(1400-10-25) (anile 56–57) London, England |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey, London, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Era | Plantagenet |

| Spouse(s) | Philippa Roet (m. 1366) |

| Children | 4, including Thomas |

| Signature | |

| |

Geoffrey Chaucer (; c. 1340s – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for The Canterbury Tales.[one] He has been called the "male parent of English language literature", or, alternatively, the "male parent of English language poesy".[2] He was the first writer to exist buried in what has since come to be called Poets' Corner, in Westminster Abbey.[3] Chaucer also gained fame as a philosopher and astronomer, composing the scientific A Treatise on the Astrolabe for his 10-twelvemonth-old son Lewis. He maintained a career in the civil service every bit a bureaucrat, courtier, diplomat, and fellow member of parliament.

Amongst Chaucer'southward many other works are The Book of the Duchess, The House of Fame, The Fable of Expert Women, and Troilus and Criseyde. He is seen every bit crucial in legitimising the literary apply of Middle English when the dominant literary languages in England were still Anglo-Norman French and Latin. His contemporary Thomas Hoccleve hailed Chaucer as "the firste fyndere of our fair langage". Almost two thousand English words are first attested to in Chaucerian manuscripts.

Life [edit]

Origin [edit]

Arms of Geoffrey Chaucer: Per pale argent and gules, a bend counterchanged.

Chaucer was born in London about likely in the early 1340s (by some accounts, including his monument, he was born in 1343), though the precise date and location remain unknown. The Chaucer family offers an extraordinary example of up mobility. His great-grandfather was a tavern keeper, his grandfather worked every bit a purveyor of wines, and his father John Chaucer rose to get an important wine merchant with a imperial appointment.[4] Several previous generations of Geoffrey Chaucer'south family had been vintners[5] [6] and merchants in Ipswich.[seven] His family proper name is derived from the French chaucier, in one case thought to hateful 'shoemaker', but now known to mean a maker of hose or leggings.[8]

In 1324, his male parent John Chaucer was kidnapped by an aunt in the hope of marrying the 12-year-old to her girl in an attempt to keep holding in Ipswich. The aunt was imprisoned and fined £250, now equivalent to nigh £200,000, which suggests that the family was financially secure.[nine]

John Chaucer married Agnes Copton, who inherited properties in 1349, including 24 shops in London from her uncle Hamo de Copton, who is described in a will dated three April 1354 and listed in the City Hustings Gyre as "moneyer", said to be a moneyer at the Tower of London. In the Metropolis Hustings Ringlet 110, v, Ric II, dated June 1380, Chaucer refers to himself equally me Galfridum Chaucer, filium Johannis Chaucer, Vinetarii, Londonie, which translates as: "Geoffrey Chaucer, son of the vintner John Chaucer, London".[10]

Career [edit]

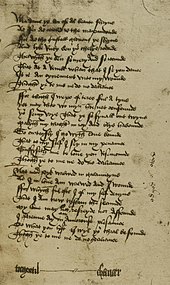

Chaucer every bit a pilgrim, in the early 15th-century illuminated Ellesmere manuscript of the Canterbury Tales

While records concerning the lives of his contemporaries William Langland and the Pearl Poet are practically not-existent, since Chaucer was a public retainer his official life is very well documented, with nearly v hundred written items testifying to his career. The first of the "Chaucer Life Records" appears in 1357, in the household accounts of Elizabeth de Burgh, the Countess of Ulster, when he became the noblewoman's folio through his father'south connections,[11] a common medieval form of apprenticeship for boys into knighthood or prestige appointments. The countess was married to Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the second surviving son of the king, Edward III, and the position brought the teenage Chaucer into the shut court circle, where he was to remain for the rest of his life. He also worked as a courtier, a diplomat, and a ceremonious retainer, every bit well as working for the king from 1389 to 1391 every bit Clerk of the King's Works.[12]

In 1359, the early stages of the Hundred Years' War, Edward Three invaded France and Chaucer travelled with Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, Elizabeth'south married man, every bit part of the English language regular army. In 1360, he was captured during the siege of Rheims. Edward paid £16 for his ransom,[13] a considerable sum equivalent to £xi,783 in 2020,[14] and Chaucer was released.

Chaucer crest A unicorn'due south head with canting arms of Roet below: Gules, three Catherine Wheels or (French rouet = "spinning bicycle"). Ewelme Church, Oxfordshire. Peradventure funeral helm of his son Thomas Chaucer

After this, Chaucer'due south life is uncertain, but he seems to have travelled in France, Kingdom of spain, and Flanders, possibly as a messenger and perchance even going on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Around 1366, Chaucer married Philippa (de) Roet. She was a lady-in-waiting to Edward 3's queen, Philippa of Hainault, and a sis of Katherine Swynford, who after (c. 1396) became the third married woman of John of Gaunt. It is uncertain how many children Chaucer and Philippa had, but 3 or iv are most usually cited. His son, Thomas Chaucer, had an illustrious career, as main butler to four kings, envoy to France, and Speaker of the House of Eatables. Thomas's daughter, Alice, married the Duke of Suffolk. Thomas'southward swell-grandson (Geoffrey'due south peachy-corking-grandson), John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, was the heir to the throne designated by Richard Three before he was deposed. Geoffrey's other children probably included Elizabeth Chaucy, a nun at Barking Abbey,[xv] [sixteen] Agnes, an attendant at Henry IV's coronation; and another son, Lewis Chaucer. Chaucer's "Treatise on the Astrolabe" was written for Lewis.[17]

According to tradition, Chaucer studied police force in the Inner Temple (an Inn of Court) at this fourth dimension. He became a member of the majestic courtroom of Edward III as a valet de chambre, yeoman, or esquire on 20 June 1367, a position which could entail a wide variety of tasks. His wife also received a pension for court employment. He travelled abroad many times, at least some of them in his function as a valet. In 1368, he may have attended the wedding of Lionel of Antwerp to Violante Visconti, girl of Galeazzo Ii Visconti, in Milan. Two other literary stars of the era were in attendance: Jean Froissart and Petrarch. Effectually this fourth dimension, Chaucer is believed to have written The Book of the Duchess in laurels of Blanche of Lancaster, the late wife of John of Gaunt, who died in 1369 of the plague.[eighteen]

Chaucer travelled to Picardy the next year as office of a military trek; in 1373 he visited Genoa and Florence. Numerous scholars such as Skeat, Boitani, and Rowland[19] suggested that, on this Italian trip, he came into contact with Petrarch or Boccaccio. They introduced him to medieval Italian poetry, the forms and stories of which he would utilize afterwards.[20] [21] The purposes of a voyage in 1377 are mysterious, every bit details within the historical record conflict. Later documents suggest it was a mission, along with Jean Froissart, to conform a spousal relationship between the future King Richard Two and a French princess, thereby ending the Hundred Years War. If this was the purpose of their trip, they seem to have been unsuccessful, as no hymeneals occurred.

In 1378, Richard 2 sent Chaucer equally an envoy (hugger-mugger dispatch) to the Visconti and to Sir John Hawkwood, English condottiere (mercenary leader) in Milan. It has been speculated that it was Hawkwood on whom Chaucer based his graphic symbol the Knight in the Canterbury Tales, for a description matches that of a 14th-century condottiere.

A 19th-century depiction of Chaucer

A possible indication that his career equally a writer was appreciated came when Edward III granted Chaucer "a gallon of wine daily for the rest of his life" for some unspecified task. This was an unusual grant, but given on a twenty-four hours of commemoration, St George'southward Day, 1374, when artistic endeavours were traditionally rewarded, it is assumed to accept been some other early poetic work. It is non known which, if whatsoever, of Chaucer's extant works prompted the advantage, just the suggestion of him as poet to a king places him equally a precursor to later poets laureate. Chaucer continued to collect the liquid stipend until Richard II came to power, later which it was converted to a monetary grant on eighteen April 1378.

Chaucer obtained the very substantial job of comptroller of the community for the port of London, which he began on viii June 1374.[22] He must take been suited for the part as he continued in it for twelve years, a long fourth dimension in such a post at that time. His life goes undocumented for much of the next ten years, but information technology is believed that he wrote (or began) most of his famous works during this period. He was mentioned in law papers of 4 May 1380, involved in the raptus (rape or seizure) of Cecilia Chaumpaigne.[23] What was meant is unclear, merely the incident seems to take been resolved quickly with an substitution of coin in June 1380 and did not leave a stain on Chaucer's reputation. It is not known if Chaucer was in the Urban center of London at the time of the Peasants' Revolt, but if he was, he would take seen its leaders pass most directly under his flat window at Aldgate.[24]

While still working every bit comptroller, Chaucer appears to take moved to Kent, being appointed equally one of the commissioners of peace for Kent, at a time when French invasion was a possibility. He is thought to accept started work on The Canterbury Tales in the early on 1380s. He likewise became a fellow member of parliament for Kent in 1386, and attended the 'Wonderful Parliament' that year. He appears to have been nowadays at near of the 71 days information technology sat, for which he was paid £24 9s.[25] On xv October that year, he gave a deposition in the case of Scrope v. Grosvenor.[26] There is no farther reference after this date to Philippa, Chaucer's married woman, and she is presumed to accept died in 1387. He survived the political upheavals caused by the Lords Appellants, despite the fact that Chaucer knew some of the men executed over the affair quite well.

On 12 July 1389, Chaucer was appointed the clerk of the rex'south works, a sort of foreman organising most of the king'south building projects.[27] No major works were begun during his tenure, merely he did conduct repairs on Westminster Palace, St. George'due south Chapel, Windsor, continued building the wharf at the Belfry of London, and built the stands for a tournament held in 1390. It may have been a hard task, simply it paid well: ii shillings a twenty-four hour period, more than three times his salary as a comptroller. Chaucer was also appointed keeper of the social club at the Rex'southward park in Feckenham Forest in Worcestershire, which was a largely honorary appointment.[28]

Later life [edit]

In September 1390, records say that Chaucer was robbed and mayhap injured while conducting the business organization, and he stopped working in this capacity on 17 June 1391. He began as Deputy Forester in the royal forest of Petherton Park in Northward Petherton, Somerset on 22 June.[29] This was no sinecure, with maintenance an important part of the job, although there were many opportunities to derive profit.

Richard Ii granted him an annual pension of twenty pounds in 1394 (equivalent to £17,834 in 2020),[thirty] and Chaucer's proper noun fades from the historical record not long subsequently Richard's overthrow in 1399. The concluding few records of his life bear witness his alimony renewed by the new king, and his taking a lease on a residence inside the shut of Westminster Abbey on 24 December 1399.[31] Henry IV renewed the grants assigned by Richard, but The Complaint of Chaucer to his Purse hints that the grants might not have been paid. The last mention of Chaucer is on 5 June 1400 when some debts owed to him were repaid.

Chaucer died of unknown causes on 25 October 1400, although the just evidence for this date comes from the engraving on his tomb which was erected more than 100 years after his death. At that place is some speculation[32] that he was murdered by enemies of Richard II or fifty-fifty on the orders of his successor Henry IV, only the case is entirely circumstantial. Chaucer was buried in Westminster Abbey in London, as was his right owing to his condition every bit a tenant of the Abbey'southward shut. In 1556, his remains were transferred to a more ornate tomb, making him the first writer interred in the area now known as Poets' Corner.[33]

Human relationship to John of Gaunt [edit]

Chaucer was a shut friend of John of Gaunt, the wealthy Duke of Lancaster and father of Henry IV, and he served under Lancaster's patronage. Near the finish of their lives, Lancaster and Chaucer became brothers-in-law when Lancaster married Katherine Swynford (de Roet) in 1396; she was the sister of Philippa (Pan) de Roet, whom Chaucer had married in 1366.

Chaucer'southward Volume of the Duchess (as well known as the Deeth of Blaunche the Duchesse)[34] was written in commemoration of Blanche of Lancaster, John of Gaunt'south get-go wife. The poem refers to John and Blanche in allegory as the narrator relates the tale of "A long castel with walles white/Be Seynt Johan, on a ryche hil" (1318–1319) who is mourning grievously later the death of his beloved, "And goode faire White she het/That was my lady name ryght" (948–949). The phrase "long castel" is a reference to Lancaster (also called "Loncastel" and "Longcastell"), "walles white" is thought to exist an oblique reference to Blanche, "Seynt Johan" was John of Gaunt's name-saint, and "ryche hil" is a reference to Richmond. These references reveal the identity of the grieving black knight of the verse form every bit John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and Earl of Richmond. "White" is the English translation of the French discussion "blanche", implying that the white lady was Blanche of Lancaster.[35]

Poem Fortune [edit]

Chaucer's brusk verse form Fortune, believed to have been written in the 1390s, is also thought to refer to Lancaster.[36] [37] "Chaucer as narrator" openly defies Fortune, proclaiming that he has learned who his enemies are through her tyranny and cant, and declares "my suffisaunce" (15) and that "over himself hath the maystrye" (fourteen).

Fortune, in turn, does not empathise Chaucer's harsh words to her for she believes that she has been kind to him, claims that he does not know what she has in shop for him in the time to come, but almost chiefly, "And eek k hast thy beste frend alyve" (32, twoscore, 48). Chaucer retorts, "My frend maystow nat reven, blind goddesse" (50) and orders her to take away those who only pretend to exist his friends.

Fortune turns her attention to 3 princes whom she implores to salvage Chaucer of his pain and "Preyeth his beste frend of his noblesse/That to som beter estat he may atteyne" (78–79). The iii princes are believed to correspond the dukes of Lancaster, York, and Gloucester, and a portion of line 76 ("as three of you or tweyne") is thought to refer to the ordinance of 1390 which specified that no royal gift could be authorised without the consent of at least two of the three dukes.[36]

Most conspicuous in this short poem is the number of references to Chaucer's "beste frend". Fortune states three times in her response to the plaintiff, "And besides, y'all still take your best friend live" (32, 40, 48); she as well refers to his "beste frend" in the envoy when appealing to his "noblesse" to help Chaucer to a higher estate. The narrator makes a fifth reference when he runway at Fortune that she shall not take his friend from him.

Religious beliefs [edit]

Chaucer's attitudes toward the Church should non be confused with his attitudes toward Christianity. He seems to have respected and admired Christians and to have been one himself, though he also recognised that many people in the church were venal and corrupt.[38] He wrote in Canterbury Tales, "now I beg all those that heed to this little treatise, or read it, that if there be anything in information technology that pleases them, they thank our Lord Jesus Christ for it, from whom proceeds all understanding and goodness."[39]

Literary works [edit]

Portrait of Chaucer (16th century). The arms are: Per pale silvery and gules, a curve counterchanged

Chaucer's first major work was The Book of the Duchess, an elegy for Blanche of Lancaster who died in 1368. Two other early works were Anelida and Arcite and The Firm of Fame. He wrote many of his major works in a prolific menstruum when he held the task of customs comptroller for London (1374 to 1386). His Parlement of Foules, The Fable of Practiced Women, and Troilus and Criseyde all date from this time. It is believed that he started The Canterbury Tales in the 1380s.[40]

Chaucer also translated Boethius' Alleviation of Philosophy and The Romance of the Rose past Guillaume de Lorris (extended by Jean de Meun). Eustache Deschamps called himself a "nettle in Chaucer'southward garden of poesy". In 1385, Thomas Usk made glowing mention of Chaucer, and John Gower also lauded him.[41]

Chaucer's Treatise on the Astrolabe describes the class and use of the astrolabe in particular and is sometimes cited as the first example of technical writing in the English, and it indicates that Chaucer was versed in science in addition to his literary talents.[42] The equatorie of the planetis is a scientific work similar to the Treatise and sometimes ascribed to Chaucer because of its language and handwriting, an identification which scholars no longer deem tenable.[43] [44] [45]

Influence [edit]

Linguistic [edit]

Portrait of Chaucer from a 1412 manuscript past Thomas Hoccleve, who may have met Chaucer

Chaucer wrote in continental accentual-syllabic metre, a style which had developed in English language literature since around the 12th century as an alternative to the alliterative Anglo-Saxon metre.[46] Chaucer is known for metrical innovation, inventing the rhyme royal, and he was one of the outset English poets to use the v-stress line, a decasyllabic cousin to the iambic pentametre, in his work, with only a few anonymous short works using it before him.[47] The arrangement of these five-stress lines into rhyming couplets, first seen in his The Legend of Good Women, was used in much of his later work and became 1 of the standard poetic forms in English. His early on influence as a satirist is also important, with the mutual humorous device, the funny accent of a regional dialect, apparently making its first appearance in The Reeve'due south Tale.

The poetry of Chaucer, forth with other writers of the era, is credited with helping to standardise the London Dialect of the Middle English linguistic communication from a combination of the Kentish and Midlands dialects.[48] This is probably overstated; the influence of the court, chancery and hierarchy – of which Chaucer was a part – remains a more probable influence on the evolution of Standard English.

Mod English language is somewhat distanced from the language of Chaucer's poems owing to the effect of the Nifty Vowel Shift some time subsequently his expiry. This alter in the pronunciation of English, nevertheless non fully understood, makes the reading of Chaucer difficult for the modern audience.

The condition of the concluding -e in Chaucer's verse is uncertain: it seems likely that during the menstruum of Chaucer's writing the final -e was dropping out of vernacular English language and that its utilize was somewhat irregular. Chaucer's versification suggests that the final -e is sometimes to be vocalised, and sometimes to be silent; nevertheless, this remains a point on which in that location is disagreement. When information technology is vocalised, most scholars pronounce it as a schwa.

Apart from the irregular spelling, much of the vocabulary is recognisable to the mod reader. Chaucer is also recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary every bit the first author to utilise many common English words in his writings. These words were probably frequently used in the language at the time but Chaucer, with his ear for common speech, is the earliest extant manuscript source. Acceptable, alkali, altercation, canter, angrily, annex, annoyance, approaching, mediation, armless, army, arrogant, arsenic, arc, artillery and aspect are just some of almost ii thou English language words first attested in Chaucer.[49]

Literary [edit]

Portrait of Chaucer by Romantic era poet and painter William Blake, c. 1800

Widespread knowledge of Chaucer'due south works is attested by the many poets who imitated or responded to his writing. John Lydgate was one of the earliest poets to write continuations of Chaucer's unfinished Tales while Robert Henryson's Testament of Cresseid completes the story of Cressida left unfinished in his Troilus and Criseyde. Many of the manuscripts of Chaucer's works contain material from these poets and afterward appreciations by the Romantic era poets were shaped past their failure to distinguish the later "additions" from original Chaucer.

Writers of the 17th and 18th centuries, such as John Dryden, admired Chaucer for his stories, just not for his rhythm and rhyme, as few critics could and then read Middle English and the text had been butchered by printers, leaving a somewhat unadmirable mess.[50] It was not until the late 19th century that the official Chaucerian catechism, accustomed today, was decided upon, largely equally a consequence of Walter William Skeat's work. Roughly 70-5 years after Chaucer's death, The Canterbury Tales was selected by William Caxton to be one of the first books to be printed in England.[51]

English [edit]

Chaucer is sometimes considered the source of the English language vernacular tradition. His accomplishment for the linguistic communication can be seen equally part of a general historical tendency towards the creation of a vernacular literature, after the case of Dante, in many parts of Europe. A parallel trend in Chaucer's ain lifetime was underway in Scotland through the work of his slightly earlier contemporary, John Barbour, and was likely to have been fifty-fifty more than general, as is evidenced by the example of the Pearl Poet in the n of England.

Although Chaucer'southward linguistic communication is much closer to Modern English than the text of Beowulf, such that (different that of Beowulf) a Mod English-speaker with a large vocabulary of archaic words may sympathise it, it differs enough that most publications modernise his idiom. The following is a sample from the prologue of The Summoner's Tale that compares Chaucer's text to a modern translation:

-

Original Text Mod Translation This frere bosteth that he knoweth helle, This friar boasts that he knows hell, And God information technology woot, that it is litel wonder; And God knows that it is little wonder; Freres and feendes been but lyte asonder. Friars and fiends are seldom far apart. For, pardee, ye han ofte tyme herd telle For, by God, you take ofttimes heard tell How that a frere ravyshed was to helle How a friar was taken to hell In spirit ones by a visioun; In spirit, once past a vision; And as an angel ladde hym upward and doun, And as an angel led him up and downwards, To shewen hym the peynes that the were, To prove him the pains that were there, In al the place saugh he nat a frere; In all the place he saw not a friar; Of oother folk he saugh ynowe in wo. Of other folk he saw enough in woe. Unto this angel spak the frere tho: Unto this angel spoke the friar thus: At present, sire, quod he, han freres swich a grace "At present sir", said he, "Accept friars such a grace That noon of hem shal come up to this place? That none of them come up to this identify?" Yis, quod this aungel, many a millioun! "Yes", said the angel, "many a one thousand thousand!" And unto sathanas he ladde hym doun. And unto Satan the angel led him downwardly. –And now hath sathanas, –seith he, –a tayl "And now Satan has", he said, "a tail, Brodder than of a carryk is the sayl. Broader than a galleon's sail. Agree up thy tayl, thou sathanas!–quod he; Concord upwardly your tail, Satan!" said he. –shewe forth thyn ers, and lat the frere se "Show forth your arse, and let the friar see Where is the nest of freres in this identify!– Where the nest of friars is in this place!" And er that half a furlong wey of space, And before one-half a furlong of space, Right so as bees out swarmen from an hyve, Only every bit bees swarm out from a hive, Out of the develes ers ther gonne dryve Out of the devil'southward arse there were driven Twenty yard freres on a route, Twenty thou friars on a rout, And thurghout helle swarmed al aboute, And throughout hell swarmed all about, And comen agayn as faste as they may gon, And came again as fast equally they could go, And in his ers they crepten everychon. And every one crept into his arse. He clapte his tayl agayn and lay ful stille. He shut his tail again and lay very nevertheless.[52]

Valentine's Day and romance [edit]

The showtime recorded association of Valentine's Day with romantic love is believed to exist in Chaucer's Parliament of Fowls (1382), a dream vision portraying a parliament for birds to choose their mates.[53] [54] Honouring the starting time anniversary of the engagement of fifteen-year-old Male monarch Richard II of England to fifteen-year-old Anne of Bohemia:

For this was on seynt Volantynys twenty-four hour period

Whan euery bryd comyth in that location to chese his make

Of euery kynde that men thinke may

And that so heuge a noyse gan they make

That erthe & eyr & tre & euery lake

So ful was that onethe was there space

For me to stonde, then ful was al the place.[55]

Disquisitional reception [edit]

Early criticism [edit]

The poet Thomas Hoccleve, who may accept met Chaucer and considered him his role model, hailed Chaucer as "the firste fyndere of our fair langage".[56] John Lydgate referred to Chaucer within his own text The Fall of Princes as the "lodesterre … off our language".[57] Around ii centuries later, Sir Philip Sidney greatly praised Troilus and Criseyde in his ain Defence of Poesie.[58] During the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, Chaucer came to be viewed equally a symbol of the nation'due south poetic heritage.[59]

Manuscripts and audition [edit]

The large number of surviving manuscripts of Chaucer's works is testimony to the enduring interest in his poetry prior to the arrival of the press press. At that place are 83 surviving manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales (in whole or role) alone, along with 16 of Troilus and Criseyde, including the personal re-create of Henry Four.[60] Given the ravages of time, it is probable that these surviving manuscripts stand for hundreds since lost.

Chaucer'due south original audience was a courtly one, and would have included women too as men of the upper social classes. Even so even before his expiry in 1400, Chaucer'southward audience had begun to include members of the rising literate, middle and merchant classes. This included many Lollard sympathisers who may well have been inclined to read Chaucer every bit one of their ain.

Lollards were particularly attracted to Chaucer'due south satirical writings well-nigh friars, priests, and other church officials. In 1464, John Baron, a tenant farmer in Agmondesham (Amersham in Buckinghamshire), was brought before John Chadworth, the Bishop of Lincoln, on charges of being a Lollard heretic; he confessed to owning a "boke of the Tales of Caunterburie" amongst other doubtable volumes.[61]

Printed editions [edit]

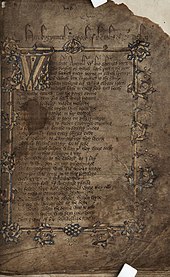

Title page of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, c. 1400

William Caxton, the first English printer, was responsible for the outset 2 folio editions of The Canterbury Tales which were published in 1478 and 1483.[62] Caxton's 2nd printing, by his own business relationship, came about because a customer complained that the printed text differed from a manuscript he knew; Caxton obligingly used the homo's manuscript as his source. Both Caxton editions carry the equivalent of manuscript authority. Caxton's edition was reprinted past his successor, Wynkyn de Worde, but this edition has no independent say-so.

Richard Pynson, the Male monarch'south Printer under Henry VIII for near twenty years, was the first to collect and sell something that resembled an edition of the collected works of Chaucer; withal, in the process, he introduced five previously printed texts that are now known non to be Chaucer'south. (The collection is really iii separately printed texts, or collections of texts, bound together as i volume.)

There is a probable connexion between Pynson's product and William Thynne'south a mere half-dozen years later. Thynne had a successful career from the 1520s until his death in 1546, equally primary clerk of the kitchen of Henry Viii, one of the masters of the imperial household. He spent years comparing diverse versions of Chaucer's works, and selected 41 pieces for publication. While at that place were questions over the authorship of some of the cloth, there is non doubtfulness this was the start comprehensive view of Chaucer's work. The Workes of Geffray Chaucer, published in 1532, was the get-go edition of Chaucer's collected works. Thynne'south editions of Chaucer's Works in 1532 and 1542 were the start major contributions to the beingness of a widely recognised Chaucerian canon. Thynne represents his edition as a book sponsored past and supportive of the king who is praised in the preface by Sir Brian Tuke. Thynne's canon brought the number of apocryphal works associated with Chaucer to a total of 28, fifty-fifty if that was not his intention.[63] As with Pynson, one time included in the Works, pseudepigraphic texts stayed with those works, regardless of their first editor's intentions.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Chaucer was printed more than than any other English author, and he was the commencement author to have his works nerveless in comprehensive unmarried-volume editions in which a Chaucer catechism began to cohere. Some scholars argue that 16th-century editions of Chaucer's Works set the precedent for all other English authors in terms of presentation, prestige and success in print. These editions certainly established Chaucer'south reputation, simply they likewise began the complicated process of reconstructing and frequently inventing Chaucer'south biography and the canonical list of works which were attributed to him.

Probably the about significant aspect of the growing apocrypha is that, beginning with Thynne's editions, it began to include medieval texts that made Chaucer appear as a proto-Protestant Lollard, primarily the Testament of Honey and The Plowman's Tale. Equally "Chaucerian" works that were non considered apocryphal until the late 19th century, these medieval texts enjoyed a new life, with English Protestants carrying on the before Lollard projection of appropriating existing texts and authors who seemed sympathetic—or malleable enough to be construed as sympathetic—to their cause. The official Chaucer of the early printed volumes of his Works was construed equally a proto-Protestant as the same was done, concurrently, with William Langland and Piers Plowman.

The famous Plowman's Tale did non enter Thynne's Works until the second, 1542, edition. Its entry was surely facilitated by Thynne's inclusion of Thomas Usk'southward Testament of Love in the start edition. The Attestation of Love imitates, borrows from, and thus resembles Usk'due south contemporary, Chaucer. (Testament of Honey besides appears to borrow from Piers Plowman.)

Since the Testament of Love mentions its author's role in a failed plot (book 1, chapter half dozen), his imprisonment, and (perhaps) a recantation of (possibly Lollard) heresy, all this was associated with Chaucer. (Usk himself was executed every bit a traitor in 1388.) John Foxe took this recantation of heresy every bit a defense of the true faith, calling Chaucer a "correct Wiclevian" and (erroneously) identifying him equally a schoolmate and shut friend of John Wycliffe at Merton College, Oxford. (Thomas Speght is careful to highlight these facts in his editions and his "Life of Chaucer".) No other sources for the Testament of Love exist—at that place is simply Thynne's construction of whatever manuscript sources he had.

John Stow (1525–1605) was an antiquarian and also a chronicler. His edition of Chaucer's Works in 1561[63] brought the apocrypha to more than than l titles. More were added in the 17th century, and they remained as late as 1810, well after Thomas Tyrwhitt pared the canon down in his 1775 edition.[64] The compilation and press of Chaucer's works was, from its showtime, a political enterprise, since it was intended to plant an English language national identity and history that grounded and authorised the Tudor monarchy and church. What was added to Chaucer often helped correspond him favourably to Protestant England.

Engraving of Chaucer from Speght'due south edition. The two superlative shields display: Per pale argent and gules, a bend counterchanged (Chaucer), that at bottom left: Gules, three Catherine Wheels or (Roet, canting arms, French rouet = "spinning bicycle"), and that at bottom right displays Roet quartering Silvery, a primary gules overall a lion rampant double queued or (Chaucer) with crest of Chaucer to a higher place: A unicorn caput

In his 1598 edition of the Works, Speght (probably taking cues from Foxe) made proficient apply of Usk'southward account of his political intrigue and imprisonment in the Testament of Love to assemble a largely fictional "Life of Our Learned English Poet, Geffrey Chaucer". Speght's "Life" presents readers with an erstwhile radical in troubled times much like their own, a proto-Protestant who somewhen came round to the king's views on religion. Speght states, "In the second year of Richard the second, the King tooke Geffrey Chaucer and his lands into his protection. The occasion wherof no doubt was some daunger and problem whereinto he was fallen by favouring some rash attempt of the common people." Under the discussion of Chaucer's friends, namely John of Gaunt, Speght further explains:

-

- All the same information technology seemeth that [Chaucer] was in some trouble in the daies of King Richard the second, every bit it may appeare in the Testament of Loue: where hee doth greatly complaine of his owne rashnesse in following the multitude, and of their hatred against him for bewraying their purpose. And in that complaint which he maketh to his empty purse, I practise find a written re-create, which I had of Iohn Stow (whose library hath helped many writers) wherein ten times more is adioined, and then is in print. Where he maketh great lamentation for his wrongfull imprisonment, wishing death to stop his daies: which in my iudgement doth greatly accord with that in the Testament of Loue. Moreouer we find it thus in Record.

Subsequently, in "The Argument" to the Testament of Dear, Speght adds:

-

- Chaucer did compile this booke as a comfort to himselfe after great griefs conceiued for some rash attempts of the commons, with whome he had ioyned, and thereby was in feare to loose the fauour of his best friends.

Speght is also the source of the famous tale of Chaucer beingness fined for beating a Franciscan friar in Armada Street, as well equally a fictitious coat of artillery and family tree. Ironically – and perhaps consciously and so – an introductory, apologetic letter in Speght's edition from Francis Beaumont defends the unseemly, "low", and earthy bits in Chaucer from an elite, classicist position.

Francis Thynne noted some of these inconsistencies in his Animadversions, insisting that Chaucer was not a commoner, and he objected to the friar-beating story. Yet Thynne himself underscores Chaucer'south support for popular religious reform, associating Chaucer's views with his father William Thynne's attempts to include The Plowman's Tale and The Pilgrim'due south Tale in the 1532 and 1542 Works.

The myth of the Protestant Chaucer continues to have a lasting touch on on a large body of Chaucerian scholarship. Though information technology is extremely rare for a modern scholar to propose Chaucer supported a religious movement that did not exist until more than a century after his death, the predominance of this thinking for so many centuries left information technology for granted that Chaucer was at least hostile toward Catholicism. This supposition forms a big function of many disquisitional approaches to Chaucer's works, including neo-Marxism.

Aslope Chaucer's Works, the almost impressive literary monument of the period is John Foxe's Acts and Monuments.... Equally with the Chaucer editions, it was critically significant to English language Protestant identity and included Chaucer in its project. Foxe's Chaucer both derived from and contributed to the printed editions of Chaucer's Works, particularly the pseudepigrapha. Jack Upland was outset printed in Foxe's Acts and Monuments, and and so it appeared in Speght'south edition of Chaucer'southward Works.

Speght's "Life of Chaucer" echoes Foxe's ain business relationship, which is itself dependent upon the earlier editions that added the Testament of Love and The Plowman'due south Tale to their pages. Like Speght's Chaucer, Foxe'due south Chaucer was also a shrewd (or lucky) political survivor. In his 1563 edition, Foxe "thought it not out of season … to couple … some mention of Geoffrey Chaucer" with a discussion of John Colet, a possible source for John Skelton'south character Colin Clout.

Probably referring to the 1542 Deed for the Advancement of True Religion, Foxe said that he

"marvel[southward] to consider … how the bishops, condemning and abolishing all fashion of English language books and treatises which might bring the people to any light of knowledge, did yet authorise the works of Chaucer to remain however and to be occupied; who, no dubiousness, saw into faith as much almost as even we do now, and uttereth in his works no less, and seemeth to exist a right Wicklevian, or else there never was any. And that, all his works virtually, if they be thoroughly advised, volition testify (albeit done in mirth, and covertly); and specially the latter end of his 3rd book of the Testament of Love … Wherein, except a man exist birthday blind, he may espy him at the total: although in the same book (as in all others he useth to do), under shadows covertly, as under a visor, he suborneth truth in such sort, equally both privily she may profit the godly-minded, and yet not be espied of the crafty adversary. And therefore the bishops, belike, taking his works only for jests and toys, in condemning other books, however permitted his books to exist read."[65]

Information technology is significant, too, that Foxe's give-and-take of Chaucer leads into his history of "The Reformation of the Church building of Christ in the Time of Martin Luther" when "Printing, being opened, incontinently ministered unto the church the instruments and tools of learning and cognition; which were good books and authors, which before lay hid and unknown. The scientific discipline of printing being found, immediately followed the grace of God; which stirred up good wits aptly to conceive the light of knowledge and judgment: by which light darkness began to be espied, and ignorance to be detected; truth from mistake, religion from superstition, to be discerned."[65]

Foxe downplays Chaucer's earthy and dotty writing, insisting that it all testifies to his piety. Material that is troubling is deemed metaphoric, while the more than forthright satire (which Foxe prefers) is taken literally.

John Urry produced the first edition of the complete works of Chaucer in a Latin font, published posthumously in 1721. Included were several tales, according to the editors, for the beginning time printed, a biography of Chaucer, a glossary of onetime English words, and testimonials of writer writers concerning Chaucer dating dorsum to the 16th century. Co-ordinate to A. S. G Edwards,

"This was the beginning collected edition of Chaucer to exist printed in roman blazon. The life of Chaucer prefixed to the volume was the work of the Reverend John Sprint, corrected and revised by Timothy Thomas. The glossary appended was also mainly compiled by Thomas. The text of Urry'southward edition has often been criticised past subsequent editors for its frequent conjectural emendations, mainly to get in adapt to his sense of Chaucer'southward metre. The justice of such criticisms should not obscure his accomplishment. His is the offset edition of Chaucer for most a hundred and l years to consult whatever manuscripts and is the first since that of William Thynne in 1534 to seek systematically to assemble a substantial number of manuscripts to establish his text. It is also the commencement edition to offering descriptions of the manuscripts of Chaucer's works, and the showtime to print texts of 'Gamelyn' and 'The Tale of Beryn', works ascribed to, but non past, Chaucer."[66]

Modernistic scholarship [edit]

Statue of Chaucer, dressed as a Canterbury pilgrim, on the corner of Best Lane and the Loftier Street, Canterbury

Although Chaucer's works had long been admired, serious scholarly work on his legacy did non begin until the late 18th century, when Thomas Tyrwhitt edited The Canterbury Tales, and it did not become an established academic discipline until the 19th century.[67]

Scholars such equally Frederick James Furnivall, who founded the Chaucer Society in 1868, pioneered the establishment of diplomatic editions of Chaucer'southward major texts, along with careful accounts of Chaucer's language and prosody. Walter William Skeat, who like Furnivall was closely associated with the Oxford English language Dictionary, established the base text of all of Chaucer's works with his edition, published by Oxford University Press. Later editions by John H. Fisher and Larry D. Benson offered further refinements, along with critical commentary and bibliographies.

With the textual issues largely addressed, if not resolved, attention turned to the questions of Chaucer's themes, structure, and audience. The Chaucer Review was founded in 1966 and has maintained its position as the pre-eminent journal of Chaucer studies. In 1994, literary critic Harold Bloom placed Chaucer among the greatest Western writers of all time, and in 1997 expounded on William Shakespeare's debt to the writer.[68]

List of works [edit]

The following major works are in rough chronological order but scholars still debate the dating of nearly of Chaucer'south output and works made up from a collection of stories may have been compiled over a long menstruum.

Major works [edit]

- Translation of Roman de la Rose, possibly extant as The Romaunt of the Rose

- The Book of the Duchess

- The House of Fame

- Anelida and Arcite

- Parlement of Foules

- Translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy as Boece

- Troilus and Criseyde

- The Legend of Good Women

- The Canterbury Tales

- A Treatise on the Astrolabe

Brusk poems [edit]

Balade to Rosemounde, 1477 impress

- An ABC

- Chaucers Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn (disputed)[69]

- The Complaint unto Pity

- The Complaint of Chaucer to his Purse

- The Complaint of Mars

- The Complaint of Venus

- A Complaint to His Lady

- The Former Age

- Fortune

- Gentilesse

- Lak of Stedfastnesse

- Lenvoy de Chaucer a Scogan

- Lenvoy de Chaucer a Bukton

- Proverbs

- Balade to Rosemounde

- Truth

- Womanly Noblesse

[edit]

- Against Women Unconstant

- A Balade of Complaint

- Complaynt D'Amours

- Merciles Beaute

- The Equatorie of the Planets – A rough translation of a Latin work derived from an Arab work of the aforementioned title. It is a clarification of the construction and utilize of a planetary equatorium, which was used in calculating planetary orbits and positions (at the fourth dimension it was believed the sun orbited the Earth). The similar Treatise on the Astrolabe, not usually doubted as Chaucer'south piece of work, in addition to Chaucer'south name as a gloss to the manuscript are the chief pieces of bear witness for the ascription to Chaucer. However, the evidence Chaucer wrote such a work is questionable, and as such is not included in The Riverside Chaucer. If Chaucer did not compose this work, it was probably written by a contemporary.

Works presumed lost [edit]

- Of the Wreched Engendrynge of Mankynde, possible translation of Innocent 3'due south De miseria conditionis humanae

- Origenes upon the Maudeleyne

- The Volume of the Leoun – "The Book of the King of beasts" is mentioned in Chaucer's retraction. It has been speculated that it may have been a redaction of Guillaume de Machaut's 'Dit dou lyon,' a story about courtly honey (a subject near which Chaucer frequently wrote).

Spurious works [edit]

- The Pilgrim's Tale – written in the 16th century with many Chaucerian allusions

- The Plowman's Tale or The Complaint of the Ploughman – a Lollard satire later on appropriated as a Protestant text

- Pierce the Ploughman's Crede – a Lollard satire afterwards appropriated by Protestants

- The Ploughman'due south Tale – its body is largely a version of Thomas Hoccleve'south "Item de Beata Virgine"[70]

- "La Belle Dame Sans Merci" – frequently attributed to Chaucer, but actually a translation by Richard Roos of Alain Chartier's verse form[71]

- The Attestation of Dear – actually by Thomas Usk

- Jack Upland – a Lollard satire

- The Floure and the Leafe – a 15th-century allegory

Derived works [edit]

- God Spede the Plough – Borrows twelve stanzas of Chaucer'due south Monk'southward Tale

Encounter too [edit]

- Chaucer (surname)

- Middle English language literature

- Poet-diplomat

References [edit]

- ^ "Geoffrey Chaucer in Context". Cambridge University Printing. 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Chaucer". Cambridge University Press. 2011. Retrieved xx April 2020.

- ^ Robert DeMaria, Jr., Heesok Chang, Samantha Zacher, eds, A Companion to British Literature, Book 2: Early on Modernistic Literature, 1450–1660, John Wiley & Sons, 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Echard, Sian; Rouse, Robert (2017). The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Uk, iv Book Set. John Wiley & Sons. p. 425. ISBN9781118396988 . Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Derek Brewer (1992). Chaucer and His Earth. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 18–19. ISBN978-0-85991-366-9.

- ^ Marion Turner (nine April 2019). Chaucer: A European Life. Princeton University Press. p. 26. ISBN978-0-691-16009-2.

- ^ Briggs, Keith (June 2019). "The Malins in Chaucer'due south Ipswich Ancestry". Notes and Queries. 66 (2): 201–202. doi:ten.1093/notesj/gjz004.

- ^ Coates, Richard, ed. (2016). "Chaucer". The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland. Oxford UP. ISBN978-0-19-967776-4.

- ^ Skeat, W. W., ed. The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. Oxford: Clarendon Printing, 1899; Vol. I, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer: Romaunt of the rose. Minor poems. Clarendon Press. 1894. pp. 13, fourteen.

- ^ Skeat (1899); Vol. I, p. xvii.

- ^ Rossignol, Rosalyn (2006). Critical Companion to Chaucer: A Literary Reference to His Life and Piece of work. New York: Facts on File. pp. 551, 613. ISBN978-0-8160-6193-8.

- ^ Chaucer Life Records, p. 24.

- ^ United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth . Retrieved two December 2021.

- ^ Power, Eileen (1988). Medieval English Nunneries, c. 1275 to 1535. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. p. 19. ISBN978-0-8196-0140-7 . Retrieved xix December 2007.

- ^ Coulton, G. One thousand. (2006). Chaucer and His England. Kessinger Publishing. p. 74. ISBN978-1-4286-4247-8 . Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ^ Rossignol, Rosalyn. Chaucer A to Z: The Essential Reference to his Life and Works. New York: 1999, pp. 72–73 and 75–77.

- ^ Holt Literature and Linguistic communication Arts. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. 2003. p. 113. ISBN978-0030573743.

- ^ Companion to Chaucer Studies, Rev. ed., Oxford Upwardly, 1979

- ^ Hopper, p. viii: He may actually have met Petrarch, and his reading of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio provided him with bailiwick thing as well as inspiration for after writings.

- ^ Schwebel, Leah (2014). "The Legend of Thebes and Literary Patricide in Chaucer, Boccaccio, and Statius". Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 36: 139–68. doi:10.1353/sac.2014.0028. S2CID 194954865.

- ^ Morley, Henry (1890) English Writers: an effort towards a history of English language literature. London: Cassell & Co.; Vol. V. p. 106.

- ^ Waymack, Anna (2016). "The Legal Documents". De raptu meo.

- ^ Saunders, Corrine J. (2006) A Concise Companion to Chaucer. Oxford: Blackwell, p. xix.

- ^ Scott, F. R. (1943). "Chaucer and the Parliament of 1386". Speculum. xviii (1): fourscore–86. doi:10.2307/2853640. JSTOR 2853640. OCLC 25967434. S2CID 159965790.

- ^ Nicolas, Sir N. Harris (1832). The controversy betwixt Sir Richard Scrope and Sir Robert Grosvenor, in the Courtroom of Chivalry. Vol. II. London. p. 404. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Morley (1890), Vol. 5, p. 245.

- ^ Forest of Feckenham, John Humphreys FSA, in Birmingham and Warwickshire Archaeology Club's Transactions and proceedings, Volumes 44–45, p. 117.

- ^ Weiskott, Eric (1 January 2013). "Chaucer the Forester: The Friar's Tale, Woods History, and Officialdom". The Chaucer Review. 47 (iii): 323–336. doi:10.5325/chaucerrev.47.3.0323. JSTOR 10.5325/chaucerrev.47.3.0323.

- ^ Ward, p. 109.

- ^ Morley (1890); Vol. V, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Jones, Terry; Yeager, Robert F.; Doran, Terry; Fletcher, Alan; D'or, Juliett (2003). Who Murdered Chaucer?: A Medieval Mystery. ISBN0-413-75910-5.

- ^ "Poets' Corner History". WestminsterAbbey.org. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Chaucer, Geoffrey (1984). "The Legend of Expert Women". In Benson, Larry D.; Pratt, Robert; Robinson, F. N. (eds.). The Riverside Chaucer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 600. ISBN978-0-395-29031-vi.

- ^ Wilcockson, Colin (1987). "Explanatory Notes on 'The Book of the Duchess'". In Benson, Larry D.; Pratt, Robert; Robinson, F. North. (eds.). The Riverside Chaucer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 966–976. ISBN978-0-395-29031-vi.

- ^ a b Gross, Zaila (1987). "Introduction to the Short Poems". In Benson, Larry D.; Pratt, Robert; Robinson, F. N. (eds.). The Riverside Chaucer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 635. ISBN978-0-395-29031-half-dozen.

- ^ Williams, George (1965). A New View of Chaucer. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 55.

- ^ "Was Chaucer in favor of the church or opposed to it? – eNotes". eNotes.

- ^ "Geoffrey Chaucer".

- ^ Benson, Larry D. (1988). "Introduction: The Catechism and Chronology of Chaucer'south Works". In Benson, Larry D. (ed.). The Riverside Chaucer (iii ed.). Oxford: Oxford Upwards. pp. xxii–xxv.

- ^ Thomas Tyrwhitt, ed. (1822). "Introductory Discourse to the Canterbury Tales". The Canterbury Tales of Chaucer. W. Pickering and R. and South. Prowett. p. 126 notation 15. ISBN978-0-8482-2624-iv.

- ^ 'The Abbey Scientists' Hall, A.R. p9: London; Roger & Robert Nicholson; 1966

- ^ Smith, Jeremy J. (1995). "Reviewed Work(s): The Authorship of The Equatorie of the Planetis by Kari Anne Rand Schmidt". The Modern Linguistic communication Review. ninety (2): 405–406. doi:10.2307/3734556. JSTOR 3734556.

- ^ Blake, N. F. (1996). "Reviewed Work(due south): The Authorship of The Equatorie of the Planetis by Kari Anne Rand Schmidt". The Review of English language Studies. 47 (186): 233–34. doi:10.1093/res/XLVII.186.233. JSTOR 518116.

- ^ Mooney, Linne R. (1996). "Reviewed Work(s): The Authorship of the Equatorie of the Planetis by Kari Anne Rand Schmidt". Speculum. 71 (1): 197–98. doi:x.2307/2865248. JSTOR 2865248.

- ^ C. B. McCully and J. J. Anderson, English Historical Metrics, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 97.

- ^ Marchette Chute, Geoffrey Chaucer of England Due east. P. Dutton, 1946, p. 89.

- ^ Edwin Winfield Bowen, Questions at Consequence in our English Oral communication, NY: Broadway Publishing, 1909, p. 147.

- ^ Cannon, Christopher (1998). The making of Chaucer'south English: a study of words, Cambridge University Printing. p. 129. ISBN 0-521-59274-seven.

- ^ "From The Preface to Fables Ancient and Modernistic". The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Stephen Greenblatt. 8th ed. Vol. C. New York, London: Norton, 2006. 2132–33. p. 2132.

- ^ "William Caxton's illustrated second edition of The Canterbury Tales". British Library. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Original e-text available online at the Academy of Virginia website, trans. Wikipedia.

- ^ Oruch, Jack B., "St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February", Speculum, 56 (1981): 534–65. Oruch'south survey of the literature finds no association between Valentine and romance prior to Chaucer. He concludes that Chaucer is likely to exist "the original mythmaker in this example." Colfa.utsa.edu Archived Apr sixteen, 2016, at the Wayback Car

- ^ Fruoco, Jonathan (2018). "Chaucer et les origines de la Saint Valentin". Conference.

- ^ Meg Sullivan (Feb 1, 2001). "Henry Ansgar Kelly, Valentine's Day". UCLA Spotlight. Archived from the original on Apr 3, 2017.

- ^ Thomas Hoccleve, The Regiment of Princes, TEAMS website, Academy of Rochester, Robbins Library

- ^ As noted past Carolyn Collette in "Fifteenth Century Chaucer", an essay published in the book A Companion to Chaucer ISBN 0-631-23590-6

- ^ "Chawcer undoubtedly did excellently in his Troilus and Creseid: of whome trulie I knowe not whether to mervaile more than, either that hee in that mistie time could run across so conspicuously, or that wee in this cleare historic period, goe and then stumblingly later on him." The text can be found at uoregon.edu

- ^ Richard Utz, "Chaucer among the Victorians," Oxford Handbook of Victorian Medievalism, ed. Joanna Parker and Corinna Wagner (Oxford: OUP, 2020): pp. 189-201.

- ^ Benson, Larry, The Riverside Chaucer (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987), p. 1118.

- ^ Potter, Russell A., "Chaucer and the Authority of Language: The Politics and Poetics of the Vernacular in Tardily Medieval England", Assays Six (Carnegie-Mellon Printing, 1991), p. 91.

- ^ "A Leaf from The Canterbury Tales". Westminster, England: William Caxton. 1473. Archived from the original on 31 Oct 2005.

- ^ a b "UWM.edu". Archived from the original on 11 Nov 2005.

- ^ "The Canterbury Tales of Chaucer: To Which are Added an Essay on his Linguistic communication and Versification, and an Introductory Discourse, Together with Notes and a Glossary by the late Thomas Tyrwhitt. Second Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1798. 2 Volumes". Archived from the original on xi November 2005.

- ^ a b The Acts and Monuments of John Foxe: With a Life of the Martyrologist, and Vindication of the Work, Volume 4. Seeley, Burnside, and Seeley. 1846. pp. 249, 252, 253.

- ^ Carlyle, E. I.; Edwards, A. S. G. (reviewer) (2004). "Urry, John (1666–1715)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford Academy Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Brewer, Derek, ed. (1978). Chaucer: The Critical Heritage. Volume 1: 1385–1837. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 230. ISBN978-0-7100-8497-two . Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Blossom, Harold (1994). The Western Catechism: The Books and School of the Ages. New York: Harcourt Caryatid. p. 226. ISBN0-xv-195747-9.

- ^ Weiskott, Eric. "Adam Scriveyn and Chaucer's Metrical Practice." Medium Ævum 86 (2017): 147–51.

- ^ Bowers, John G., ed. (1992). "The Ploughman'southward Tale: Introduction". The Canterbury Tales: Fifteenth-Century Continuations and Additions. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications.

- ^ Symons, Dana M., ed. (2004). "La Belle Dame sans Mercy: Introduction". Chaucerian Dream Visions and Complaints. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications.

Bibliography [edit]

- Biggs, David; McGivern, Hugh; Matthews, David; Murrie, Greg; Simpson, Dallas (1999) [1997]. Burton, T. Fifty.; Greentree, Rosemary (eds.). Chaucer's Miller's, Reeve's, and Melt's Tales: An Annotated Bibliography 1900-1992. The Chaucer Bibliographies. Vol. 5. Toronto, Buffalo, and London: Academy of Toronto Printing in association with the University of Rochester. doi:10.3138/9781442672895. ISBN9781442672895. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2tv0bw.

- Fruoco, Jonathan, ed. and transl. (2021). Le Livre de la Duchesse: oeuvres complètes (Tome I). Paris: Classiques Garnier, ISBN 978-2406119999.

- Benson, Larry D.; Pratt, Robert; Robinson, F. N., eds. (1987). The Riverside Chaucer (3rd ed.). Houghton-Mifflin. ISBN978-0-395-29031-six.

- Crow, Martin 1000.; Olsen, Clair C. (1966). Chaucer: Life-Records.

- Hopper, Vincent Foster (1970). Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (Selected): An Interlinear Translation . Barron's Educational Serial. ISBN978-0-8120-0039-ix.

- Hulbert, James Root (1912). Chaucer'southward Official Life. Collegiate Press, G. Banta Pub. Co. p. 75. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Morley, Henry (1883). A Kickoff Sketch of English Literature. Harvard University.

- Skeat, Westward. W. (1899). The Consummate Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Speirs, John (1951). Chaucer the Maker. London: Faber and Faber.

- Turner, Marion (2019). Chaucer: A European Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Fruoco, Jonathan (2020). Chaucer'southward Polyphony. The Modern in Medieval Poetry. Berlin-Kalamazoo: Medieval Found Publications, De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-5015-1849-2.

- Ward, Adolphus West. (1907). Chaucer. Edinburgh: R. & R. Clark.

- Akbari, Suzanne Conklin; Simpson, James, eds. (2020). The Oxford handbook of Chaucer. Oxford. ISBN978-019-9582-655.

External links [edit]

- Chaucer Bibliography Online

- Works by Geoffrey Chaucer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Geoffrey Chaucer at Internet Annal

- Geoffrey Chaucer on In Our Time at the BBC

- Educational institutions

- Chaucer Folio by Harvard University, including interlinear translation of The Canterbury Tales

- Caxton'south Chaucer – Complete digitised texts of Caxton'southward ii primeval editions of The Canterbury Tales from the British Library

- Caxton's Canterbury Tales: The British Library Copies An online edition with complete transcriptions and images captured by the HUMI Project

- Chaucer Metapage – Project in add-on to the 33rd International Congress of Medieval Studies

- Chaucer and his works: Introduction to Chaucer and his works (Descriptions of books with images, University of Glasgow Library)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffrey_Chaucer

0 Response to "The Complaint of Venus Read in Middle English"

Enregistrer un commentaire